|

|

Datuk Dr. Jeffrey Kitingan is the Chairman of STAR Sabah and State Assemblymen for N33, Bingkor, Sabah.

He also contested in P180, Keningau garnering 11900 strong votes

|

Oftentimes, it is the easier and safer path to pretend that certain problems, particularly those that touch on critical and sensitive issues, do not exist. If we were to do this, we shall have proved untrue to ourselves as leaders of our people. It is in this context, therefore, that the author prepared this Memo as his contribution to the removal of hindrances to the development of cordial and enduring Federal-State relations. It is only when Federal and State leaders are unafraid to tackle the most sensitive issues may we achieve true nationhood.

I. INTRODUCTION

1. This document represents a memorandum (hereafter called the ‘Memo’) prepared by Dr. Jeffrey G. Kitingan at the request of the Federal Government through the press statement of the Deputy Prime Minister, Encik Ghafar Baba. This Memo addresses a wide range of problems pertaining to Federal-State relations and is divided into seven major parts. First, it provides a background to the events that led to the preparation of the Memo. Second, it outlines the contentious issues of Federal-State relations that will be addressed by the Memo. Third, it gives a selective, historical review of the Malaysia Project for the purpose of highlighting the status of Sabah in the Federation. Fourth, it reviews critically the Twenty Points, particularly with regard to the manner in which they were incorporated into the Inter-Governmental Committee (IGC) Report, the Malaysia Agreement and the Federal Constitution and the manner in which they were subsequently implemented. The aim is to highlight specific cases of deviations. Fifth, it exposes selected cases of political interference by the Federal Government in State politics. Sixth, it presents a series of recommendations which the Federal Government could adopt and implement to enhance its relations with the State of Sabah. Finally, it presents the conclusion of the Memo, explaining the motivation of preparing the Memo.

2. The series of events and public remarks that led to the preparation of the Memo emanated from a New Year message by Dr. Kitingan when, in his personal capacity, he outlined the principal areas of action which the Sabah Government should pay attention to in the coming years. According to Dr. Kitingan, the areas of concern relate to:

(a) Improving Federal-State relations.

(b) Resolving the refugee problem.

(c) Strengthening programmes for economic recovery.

(d) Improving efficiency of government machinery.

(e) Improving information exchange between the Government and the general public.

The Daily Express picked up what was said about Federal-State relations on January 3, 1986. The most commonly quoted passages are as follow:

“Wrongly or rightly, it is widely perceived that the Federal leadership has been influencing the development of political events in Sabah to the detriment of the ruling party.”

“He pointed out another possible source of dissatisfaction, that is, the alleged overcentralisation of public administration and lack of State participation in policy formulation at national level.”

“He said, while the desire of the Federal Government to standardise national policies should be recognised, in the case of Sabah, the application of such policies must be consistent with the terms of the Malaysia Agreement.”

“This meant that the Federal treatment of Sabah and perhaps, Sarawak, must necessarily be different from the other States in the Peninsular, if the rights of Sabahans and Sarawakians were to be respected.”

“This common perception of Federal’s meddling with local affairs, if uncorrected, is unlikely to lead to harmonious relationship between the people of Sabah and the Federal Government in the long run.”

“Federal and State leaders should cultivates and foster patriotism among Sabahans through mutual respect to wipe out any perception of Federal domination and imposition on the people in the State.”

3. Subsequent to the Daily Express report on the subject, Dr. Kitingan received a great deal of attention. Many supported his view, others criticised him for bringing up the issue. The Deputy Prime Minister invited Dr. Kitingan to send him a memo listing all areas of deviations and to discuss thses with the Federal Government. It should be stressed here that the series of public remarks uttered in response to Dr. Kitingan’s initial statements were biased towards the issue of the Twenty Points, whereas he was more concerned about general problems of Federal-State relations, including (but not limited to) those that are intricately linked with the contents and spirit of the Malaysia Agreement.

II. ISSUES IN QUESTION AND THE OBJECTIVES OF THE MEMORANDUM

4. The substantial amount of debate and public discussion focused on the Twenty Points as a result of Dr. Kitingan’s remarks on problems of Federal-State relations goes to show that many Malaysians od Sabah origin are deeply concerned about historical issues which determine their basic rights and status within the Federation. Of Course, one may view this as perfectly ‘normal’ in that as a federated nation develops, both in the political and economic spheres, its citizens tend to become more conscious of their identity and sovereign rights and hence may press for demands which they consider as rightly theirs. In Sabah, however, there is evidence to show that its citizens’ tendency to question their status within the Federation has been fueled by actions that originate from Kuala Lumpur – actions which are detrimental to harmonious Federal-State relations.

5. As will be shown in this Memo, these actions do not only take the form of direct and indirect interferences by Kuala Lumpur in State affairs but, more importantly, through it failure, intended or otherwise, to observe and honour certain safeguards, guarantees and assurences granted to Sabah at the time of the Malaysia Project. For these reasons, it will be essential in this Memo to go back to history and examine briefly some of the aspirations and vision that the founders of Malaysia had in mind when they set the agenda for nation-building. The ensuing discussion on the historical side will be selective in its re-collection of events by focusing on the aspirations and promises which the State and national leaders conceived for the people of Sabah.

6. The principal issues in question are, therefore, very basic. The first issue relates to the statement that “Sabah has achieved its independence through Malaysia.” Several questions must be posed here. What was the Sabah leaders’ understanding of the term Independence? Does self-government and self-determination carry the same meaning today as they did then? What was the understanding on the status of Sabah in the Federation of Malaysia? Was it one of the four components (now three) or was it one of the fourteen states (now thirteen)? If the former was the Federation – a Federation of equal partnership as indicated by Tunku Abdul Rahman – was it the intention of the founding fathers to merge Sabah with Malaya or was it intended to assimilate Sabah into Malaya? If Sabah is accepted as having gained independence through Malaysia, should it maintain its own character and identity as such? If Sabah is to be an equal partner, how should the economic cake and political representation be shared? The answer to this question is important because it forms the basis for Federal-State relations and serves as a guide to the decision making process at Kuala Lumpur.

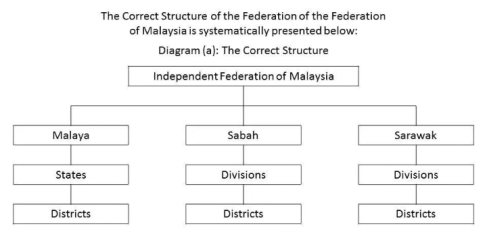

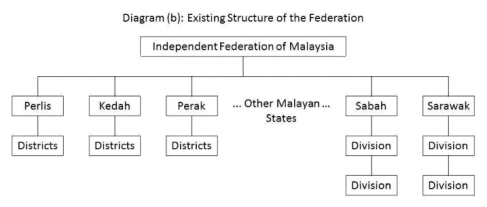

7. The second issue involves the examination of the manner in which the Federal government has deviated from implementing specific assurances provided for in the Twenty Points, including those that were subsequently incorporated in the IGC and Malaysia Agreement. In this regards, it should question whether it is possible, within the framework of a strong Federal government, to allow the state Government to maintain its autonomy in specific areas of government granted in the Malaysia Agreement. Hence, one needs to ask whether the spirit of good faith, mutual trust and sincerity expressed during the negotiations at the formation of Malaysia still exist today.

8. Third, it is essential to re-address the late Tun Fuad Stephens’ question concerning the validity of the Malaysia Agreement in the light of Singapore’s departure from the Federation which occurred without consultation and ratification by the remaining signatories to the Agreement.

9. Given the above issues, it is now appropriate to state formally the specific objectives of tis Memo. These are:

(a) To establish the basis for the development of a strong harmonious and enduring Federal-State relations.

(b) To examine possible areas in the Twenty Points as incorporated in the IGC Report, Malaysia Agreement and Federal Constitution where deviations, changes or amendments have occurred against the spirit and intent for which they were originally drawn.

(c) To identify other possible causes of poor Federal-State relations; and

(d) To outline specific recommendations for improving relations between the Federal and Sabah/Sarawak and the people of the two territories.

10. When preparing this Memo, the author is guided principally by his intense and sincere desire to portray the present sentiments and feelings of Sabahans towards the Federation, as accurately as possible, to the leaders at Kuala Lumpur. He feels compelled by the current developments in the State to convey those pervasive uneasy feelings in a frank, honest and straight forward manner,. Should blunt words be used in several places in the Memo, it is basically because the use of other more ambiguous and evasive substitute may cloud the issues and problems in question. Where remarks are made about the attitude and leadership qualities of certain leaders, they are solely for the purpose of illustration or to make a point and not intended to be a malicious attack on their person or character. The author strongly believes that our present leaders can profit much from both the successes and failures of past leaders in fostering closer Federal-State relations. Moreover, objective assessment of past events would guide us in the right direction towards developing a stronger and more resilient, multiracial society.

III. THE MALAYSIA PROJECT AND THE STATUS OF SABAH IN THE FEDERATION

11. On 27 May, 1961, Y.T.M Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj, the Prime Minister, Federation of Malaya, at a press luncheon in Singapore made the proposal that a Federation of Malaysia should be created, comprising the eleven States of Malaya, Singapore, the three Borneo territories of Sarawak, North Borneo and Brunei. The regularly quoted words of the Tunku were as follows:

“… Sooner or later she (Malaya) should have an understanding with the peoples of Singapore, North Borneo, Brunei and Sarawak… these territories can be brought closer together in a political and economic cooperation” (speech made by Tunku Abdul Rahman on 27 May, 1961 to the Foreign Correspondents of Southeast Asia in Singapore).

Later, on 16 October, 1961, the Tunku explained to the Malayan Parliament the motivation and framework for the formation of the Federation of Malaysia as follows.

“… When considering the concept of Malaysia it is necessary to keep in mind that the independent Federation of Malaya has to take note of three separate elements and the special interests of each. These three elements are the State of Singapore, which is almost completely self-governing, the three Borneo territories which are still colonies, and the United Kingdom which has special obligations or duties in relation to the people of these areas.”

“… I will turn now to the problem of the Borneo territories in relation to the concept of Malaysia. These territories do not present the same complexity in the implementation of the concept as Singapore does. In a broad sense, it could be stated that the question is much simpler there, in fact so much simpler that they present a special difficulty of their own. The three Borneo territories have two political factors in common. First… vestiges for British colonialism. Second… their constitutional development has been very slow”(speech by Tunku Abdul Rahman, Prime Minister, the Federation of Malaya, in the Federal Parliament on 16 October, 1961).

12. Amidst all the rhetoric which accompanied the campaign for an enlarged Federation, the plan to include the States of North Borneo, Sarawak and Brunei was, however, somewhat coincidental, for what the Tunku really wanted was Singapore. Nevertheless, the Tunku had one genuine aim for the Borneo territories – independence from the British colonialism. As he put it then:

“… it is our duty to help bring about an end to any form of colonialism. The very concept of Malaysia Plan is an effort to end colonialism in this region of the world, in a peaceful and constructive manner. We in Malaya won our independence by peaceful means and we are sure that the people of the Borneo territories would like to end their colonial status and obtain independence in the same way.

“… the important aspect of the Malaysia ideal as I see it, is that it will enable the Borneo territories to transform their present colonial status to self-government for themselves and absolute independence in Malaysia simultaneously.”

13. On the British Government’s side, it was not an issue to grant independence to the Borneo States (North Borneo, Sarawak and Brunei), since the British Government had decided to allow these territories to attain their own independence ultimately. The question was one of timing and the form it should take. As one document puts it:

“… The declared aim of the British Government is to grant independence to all its colonial territories as soon as they are ready for it. Hitherto this has been thought of simply as independence fo North Borneo standing by itself or, more recently, in association with Sarawak.”

“… It is the view of the British Government that provided satisfactory terms of merger can be worked out, the plan for Malaysia offers the best chance of fulfilling its responsibility to guide the Borneo territories to self-government in conditions that will secure them against dangers from any quarters.”

“… Malaysia offers for them all the prospect of sharing in the destiny of what the British Government believes will be a great, prosperous and stable Independent State within the Commonwealth” (Extract from “North Borneo and Malaysia” published by Authority of the Government of North Borneo, Jesselton, February 1962)

14. Even at the point in time, there was considerable concern that the notion of ‘independence through Malaysia’ might not be the sort of independence that the Borneo States were looking for. There were those who were concerned about neo-colonialism. On this issue the Tunku had the following to say:

“… One reaction in the Borneo territories was that the Malaysia concept was an attempt to colonise the Borneo territories. The answer to this was, as I said before, it is legally impossible for the Federation to colonise because we desire that they should join us in the Federation in equal partnership, enjoying the same status between one another, so there is no fear that Malaysia will mean that there will be an imposition of Islam on Borneo… everybody is free to practise whatever religion.” (Extract of speech by Tunku Abdul Rahman, Prime Minister of the Federation of Malaya, in the Federal Parliament on 16 October 1961)

In addition, the colonial government of North Borneo had cautioned that:

“… It is necessary, therefore, for the people of North Borneo to consider what powers they are prepared to concede in order to bring Malaysia into being. It is understood that there should be widespread apprehension lest, in practice, Malaysia would mean that the people of North Borneo would have far less control over their own affairs than they exercise already, and that North Borneo would be relegated to the position of a relatively powerless province of a strong Federal Government situated 1,000 miles away” (Extract from ‘North Borneo and Malaysia’)

For this reason, in the same speech the Tunku raised the issue of constitutional safeguards:

“… Moreover in our future constitutional arrangement the Borneo people can have a big say in matters on which they feel very strongly, matters such as immigration, customs, Borneonisation, and control of their State franchise rights.” (Speech by Tunku Abdul Rahman in the Federal Parliament on 16 October 1961)

The need for consultation and non-interference in the normal affairs of the Borneo State was highlighted by the Tunku.

“… One very strong feeling was that they must be consulted on the future of their people and the future of the country. I have said on more than one occasion that Malaya can only accept Borneo people from an expression of their own free will to join us.”

Other observers noted that:

“… In conversation with members of the North Borneo delegation to the Malaysia Solidarity Consultative Committee he (the Tunku) has made it abundantly clear that he has no wish to interfere in the internal affairs of North Borneo and is willing to consider sympathetically any proposal for the management by the people of this country of their own internal affairs.” (IGC Report)

Even the Colonial Government of North Borneo cautioned strongly that:

“… It would, indeed, be against the long-term interest of the Malayan Government to insist on excessive control against the wishes of the people of the Borneo territories, which would over the course of the years build up resentment and discontent leading to a repetition within Malaysia of the internal stresses and strains which, in recent years, have become apparent within the framework of Indonesia, and, more recently still, have culminated in the secession of Syria from the United Arab Republic. (‘North Borneo and Malaysia’)

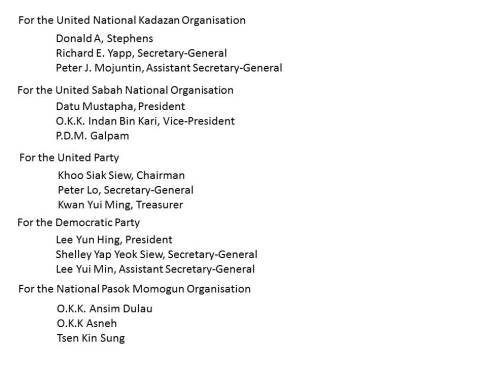

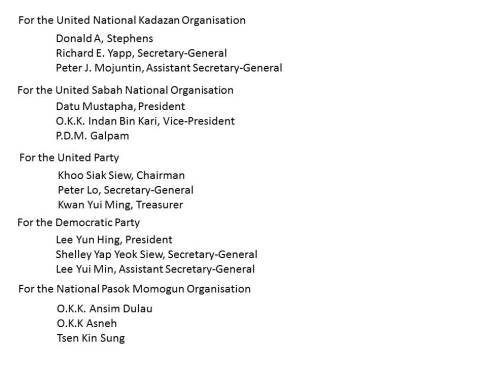

15. Arising from the various public statements on the need for safeguards and conditions, formal steps were undertaken to identify these safeguards and to present them for discussion by political leaders and officials of all the parties involves. A strong starting point for these discussions was the submission of a Memorandum containing the ‘Twenty Points’ on 29th August, 1962 by the leaders of five newly formed political parties (The United Kadazan Organisation, The United Sabah National Organisation, The United Party, The Democratic Party and The National Pasok Momogun organisation). The Memorandum was a joint declaration setting out the basis on which Malaysia would be acceptable in North Borneo and embodying minimal safeguards in the form of Twenty Points which the parties considered necessary for North Borneo in its entry into Malaysia. The signatories to the 20 Points Memorandum were as follows:

The principles of the 20 Points were accepted in total. The implementation of the Twenty Points was discussed at length by the IGC and most of them were subsequently taken up and incorporated in the Malaysia Agreement.

16. Discussion of the details of the various safeguards and conditions is the subject of the next section of this Memo. Suffice it to emphasize here that security consideration and economic development were important motivations for support for the proposed Federation, which was identified with independence in the mind of the People. Certainly, there existed as expectation that the new Federation will be conducive to harmony among ethnic groups and economic advancement in the rural areas.

17. The process of bringing the Malaysia Project to fruition was of course a lengthy and arduous task. It involved, among others, the Cobbold Commission of Inquiry, IGC and UN Malaysia Mission. While these bodies all came to the conclusion that the leaders and people of Sabah generally “expressed strong support for the establishment of the Federation of Malaysia” it is crucial to note that their views were by no means unanimous. The main finding of the Commission of Inquiry deserves to be mentioned here:

“… In accessing the opinion of the peoples of North Borneo and Sarawak we have only been able to arrive at an approximation. We do not wish to make any guarantee that it may not change in one direction or the other in the future.”

“… About one third of the population in each territory strongly favours early realisation of Malaysia without too much concern about terms and conditions. Another third, many of them favourable to the Malaysia Project, asked with varying degrees of emphasis, for conditions and safeguards varying in nature and extent: the warmth of support among this category would be markedly influenced by a firm expression of opinion by Governments that the detailed arrangement eventually agreed upon are in the best interests of the territories. The remaining third is divided between those who insist on independence before Malaysia is considered and those who would strongly prefer to see British rule continue for some years to come…

There will remain a hard core, vocal and politically active, which will oppose Malaysia on any terms unless it is preceded by independence and self-government; the hard core might amount to near 20 per cent of the population of Sarawak and somewhat less in North Borneo.” (Extract of the Commission of Inquiry, North Borneo and Sarawak, 1962 – HMSO SMND, 1974).

The reservation exhibited by the people of Sabah (about two-thirds) as regards the proposed Federation served to emphasise the importance they attached to the provision of specific safeguards and conditions because of the uncertainty of their future in the enlarged Federation. The issue of safeguards and their fulfilment by the Federal government was very basic to their decision to form the Federation. Any violation of the safeguards would constitute a violation of the conditions upon which the State agreed to be a party to the formation of the Federation of Malaysia.

18. In retrospect, the vision of the Tunku, the aspirations of the Sabahan leaders and the consent of the Colonial Government as regards the formation of the Federation of Malaysia all converged on the important conclusion that:

(a) Sabah would participate in the formation of the Federation in equal partnership with Malaya, Singapore and Sarawak;

(b) The Federal government would not interfere in the internal affairs of Sabah, which would also be consulted on the future of her people and the future of Malaysia;

(c) There would be autonomy in specific areas of government;

(d) The new Federation promised an independence state and an improved economic well-being to the people of Sabah.

IV. THE TWENTY POINTS AND THE DEVIATIONS IN IMPLEMENTATIONS

19. As already stated, the Twenty Points Memorandum came into being when five political parties representing the people of Sabah presented a united stand on theminimum safeguards considered by the Sabahan leaders as crucial, the acceptance of which would pave the way for the formation of the new Federation. This document is truly important because it embodies the needs and aspirations of the people of Sabah.

20. The views expressed in the Twenty Points were the basis of Sabah’s acceptance to be part of the Federation of Malaysia. Most of the Twenty Points were incorporated upon deliberation, into the Inter-Governmental Committee Report and the Malaysia Agreement.

21. It should be stressed here that while much energies and time were expended in deliberations on the constitutional safeguards, the mechanism for their implementation and protection from change, amendment or deviation was conveniently disregarded. Hence, with a powerful and all-embracing Malayan Government, insufficient attention was paid by the Sabah negotiating team as to how the assurances, undertaking and promises could be implemented once Sabah became a component of the Federation of Malaysia. Little attention was also paid to the subject of recourse which Sabah might take against the Federal government in the event of breach of the constitutional safeguards and assurances. The safeguards were negotiated in the spirit of a gentlemen’s agreement. It can be inferred that the absence of any provision in the 20 Points for a possible recourse which Sabah could take against the Federal government in the event of a breach of the constitutional safeguards and conditions was indicative more of the faith of Sabah’s leaders in former Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman and the Federal government’s assurances rather than the lack of foresight. To them a gentlemen’s agreement was sufficient guarantee, although later events have proven Sabah’s leaders wrong.

22. The Twenty Points are presented below together with a statement of their status in the context of the IGC, Malaysia Agreement and Federal Constitution. Comments pertaining to deviations in implementation, where appropriate, are outlined after the presentation of each point.

22.1 Point 1: Religion

While there was no objection to Islam being the national religion of Malaysia there should be no State religion in North Borneo, and the provision relating to Islam in the present Constitution of Malaya should not apply in North Borneo.

Comments:

In the IGC Report this point was taken up in the form of the provision that “Islam is the religion of the Federation” which essentially reaffirmed Article 3(1) of the Federal Constitution.

A contravention of this point occurred when the former Chief Minister of Sabah, Tun Mustapha enabled the passage of a constitutional amendment in the State Constitution thereby making Islam the State religion in 1973. It is well-known that Tun Mustapha actively discriminated against the promotion of other religions by expelling their missionaries. By this act, religious freedom which was intended by this point was abrogated in favour of Islam. His successor, Datuk Harris Salleh, also actively engaged in proselytization by using Islam as an instrument to grant favours to new converts. It was widely perceived by the general public that the actions of both Tun Mustapha and Datuk Harris were motivated by their need to strengthen their own political position vis-à-vis Kuala Lumpur.

In the case of the present Government, it tries to restore religious freedom by dealing with all religions equally but this is perceived as being anti-Islam. This is despite the fact that the State Legislative Assembly in 1986 inserted a new Article 5B “to confer on the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong the position of the Head of Islam in Sabah.”

Today, the status of Islam as the State religion has made it an instrument of political bigotry and provides a justification for religious polarisation and discrimination.

One may, of course, argue that the deviation that has occurred with respect to this particular point was caused by the State and not by the Federal authorities. This is too simplistic a view. As will be shown in Section V of the Memo, an examination of the Federal Government’s dealings with the State during the reign of the previous Chief Ministers shows numerous subtle interferences in Sabah’s political and administrative affairs by Kuala Lumpur, some of which are manifested in the form of administrative measures and decision making by Federal agencies. As a consequence, many constitutional amendments made at the State level which led to the dilution and surrender of several safeguards, were initiated and influenced by Federal Government. (e.g. Federalisation of Labuan).

22.2 Point 2: Language

(a) Malay should be the national language of the Federation;

(b) English should continue to be used for a period of time of ten years after Malaysia Day;

(c) English should be the official language of North Borneo, for all purposes, State or Federal, without limitation of time.

Comments:

Tun Mustapha’s administration changed the status of English by passing a bill, introducing a new clause 11A into the State Constitution, making Bahasa Malaysia the official language of the State Cabinet and State Legislative Assembly. At the same time, the National Language (Application) Enactment 1973 was passed purporting to approve the extension of an Act of parliament terminating or restricting the use of English language for other official purposes in Sabah. This is putting the cart before the horse, because the National Language Act 1963/67 was only amended in 1983 to allow it to be extended to Sabah by State Enactment. But, no such State Enactment has been passed. Therefore, the National Language Act 1963/67 is still not in force in Sabah. Nevertheless, the above amendments have brought about the following consequences:

(a) Many civil servants who were schooled in English are now employed as temporary or contract officers because of their inability to pass the Bahasa Malaysia examination.

(b) The change in the medium of instruction in schools affected the standard of teaching due to lack of qualified Bahasa Malaysia teachers.

(c) The teaching of other native languages has been relegated to the background.

Many Sabahans believe that the Constitutional Bill passed in 1973 to erode this safeguard was probably made on the advise and influence of syed Kechik, who was regarded as the KL’s man in Sabah. (See Ross-Larson(1980)).

22.3 Point 3: Constitution

Whilst accepting that the present Constitution of the Federation of Malaya should form the basis of the Constitution of Malaysia, the Constitution of Malaysia should be a completely new document drafted and agreed in the light of free association of States and should notbe a series of amendments to a Constitution drafted and agreed by different States intotally different circumstances. A new Constitution for North Borneo was, of course, essential.

Comments:

It is obvious that the Sabah and Sarawak negotiating teams were of the opinion that they were joining in the Federation of Malaysia as equal partners, namely Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak. However, the request for a completely new Constitution was not granted thereby deviating from the basic agreement. The reasons offered were:

(a) Due to time constraint. The drafting of a completely new Constitution would take a long time to complete.

(b) The Sabah negotiating team recognised the amount of time and energy required to draft a new Constitution.

From the foregoing, it is clear that during the negotiation, the State leaders had shown complete trust and confidence in the capabilities of the Malayan leadership in honouring the assurances and promises given them. As a result, minimum fuss was made of the necessity of casting those promises and assurances in enforceable terms to be duly incorporated into official documents, complete with legal and constitutional recourse in the event of breaches. Furthermore, the readiness with which the State leaders consented to the use of Federal Constitution of Malaya as a basis on which new amendments were to be incorporated also illustrates the trusting nature of the State leaders then. However, the speed with which the formation of the Federation of Malaysia was hurriedly implemented, at a time when the people of Sabah were still constitutionally backward, leaves many present-day better educated Sabahans to question the extent of participation of the Sabahan leaders in the entire negotiation process. For such an important undertaking which affects the future of the people of Sabah, certainly more time should been given.

An important agreement reached by the Inter-Governmental Committee was that in certain aspects, the requirement of Sabah and Sarawak could appropriately be met by undertaking or assurances to be given by the government of the Federation of Malaya rather than by constitutional provision. Still, this was a clear deviation from what was requested in the Twenty Points.

22.4 Points 4: Head of the Federation

The Head of State in North Borneo should not be eligible for election as Head of the Federation.

Comments:

Since only a Ruler is eligible to be elected as the Head of the Federation in the Malayan Constitution, there was no necessity to make specific provision for the exclusion of the Head of the State of Sabah from election as Head of the Federation.

22.5 Point 5: Name of Federation

“Malaysia” but not “Melayu Raya”

Comments:

This point was incorporated into the IGC Report and subsequently into the Federal Constitution.

22.6 Point 6: Immigration

Control over immigration into any part of Malaysia from outside should rest with the Federal government but entry into North Borneo should also require the approval of the State government. The Federal government should not be able to veto the entry of persons into North Borneo for State government purposes except on strictly security grounds. North Borneo should have unfettered control over the movement of persons, other than those in Federal government employ, from other parts of Malaysia into North Borneo.

Comments:

While it was agreed in the IGC Report that the Immigration department should be a Federal department, the State should have absolute control of immigration to Sabah from within Malaysia.

22.7 Point 7: Right of Secession

There should be no right to secede from the Federation.

Comments:

There was absolutely no reason or need for this point to be listed since it is not a safeguard for the State but for the Federal government. Nevertheless, the amazing readiness of the five political parties to include this as one of the Twenty Points reflected their firm belief that the ‘marriage’ would be a permanent one. Their decision to concede the right to secession was no doubt motivated by the promise of improved economic well-being that the new Federation would bring and the respect with which the Federal government would place on agreed safeguards and assurances.

22.8 Point 8: Borneonisation

Borneonisation (Sabahanisation) of the public services should proceed as quickly as possible.

Comments:

As a consequence of Federal’s control on pensions (Article 112 of the Federal Constitution and Para 24 of the IGC Report), all promotions in the Federal department and creation of new posts in the State require Federal approval due to the “pension factor.”

An examination of existing records shows that the number of federalised departments or agencies in Sabah has increased 4 times since Independence. By 1985 there were 62 Federal departments and agencies in Sabah, of which more than 90 per cent is currently headed by Semenanjung officers. According to employment record, there are more than21,000 Semenanjung officers working in government offices in Sabah. This is a clear deviation of the Twenty Points and IGC safeguards.

The usual justification used by the Federal Government to engage officers from Semenanjung to fill the federalised government positions is the lack of qualified Sabahans. However, it is found that even officers in the C and D categories are still being imported into the State from Kuala Lumpur. Furthermore, there has been no conscious plan to train prospective Sabahans to take over senior posts from these Semananjung officers.

At a time when some 800 graduates and thousands of school leavers in Sabah are unemployed, the existence of a large number of civil servants from Semenanjung serving in government departments gives many Sabahans the feeling that they have been deprived of employment opportunities which, in the context of the Twenty Points, are rightfully theirs.

22.9 Point 9: British Officers

Every effort should be made to encourage British Officers to remain in the public services until their places can be taken by suitably qualified people from North Borneo.

Comments:

This point was taken up and discussed extensively in the IGC Report.

22.10 Point 10: Citizenship

The recommendations in paragraph 148(k) of the Report of the Cobbold Commission should govern the citizenship rights of persons in the Federation of North Borneo subject to the following amendments:

(a) Subparagraph (I) should not contain the provision as to five years residence;

(b) In order to tie up with our law, subparagraph (II)(a) should read “seven out of ten years” instead of “eight out of twelve years”;

(c) Subparagraph (III) should not contain any restriction tied to the citizenship of parents – a person born in North Borneo after Malaysia must be a Federal Citizen.

Comments:

It is public knowledge that there is a significant number of Sabahans who were born before Malaysia Day is still having problems acquiring citizenship. Furthermore, many natives in the interior regions of the State are still holder of red I.C. because of the problems of verifying their birth.

It is also common knowledge that certain categories of refugees and illegal immigrants in Sabah have been issued with blue I.C. thus conferring upon them citizenship status and enabling them to vote in elections. This occurred particularly during the tenure of the previous State governments. A reliable source indicates that some 198,000 of these refugees have been issued with blue I.C.

According to a newspaper report, which was subsequently confirmed, police forces acting on public complaint raided Peting Bin Ali’s house in Sandakan on 16 November, 1979 and discovered that he was in possession of facilities to issue blue ICs. It is believed that the operators were collaborating with certain registration personnel in Kuala Lumpur. Most surprisingly the culprit was not prosecuted for committing such a grave crime against all the citizens of the country.

The process by which these illegals are registered by the Federal agencies for subsequent issuance of blue ICs, without due reference to the State, is considered by Sabahans as usurpation of the State’s immigration authority. This is a clear deviation from the safeguard on immigration and control of its franchise rights. Furthermore, the use of Labuan as an entry point to Sabah without immigration check, effectively removes immigration control from the State government.

22.11 Point 11: Tariff and Finance

North Borneo should have control of its own finance, development funds and tariffs.

Comments:

This illustrates the true feeling of the Sabah leaders concerning Malaysia. They saw Sabah as equal partner in Malaysia. With its vast natural resources not yet fully tapped and the promise of rich oil discoveries, the Sabah leaders foresaw that the State would have adequate financial resources to cater for its socio-economic development. Today, all proceeds of revenue other than those listed in Part III of the Ten Schedule are accrued to the Federal government. These include personal income tax, corporate tax, export and import duties, petroleum royalty, etc. The State government derives its incomes primarily from timber exploitation, copper mining, and since 1974, from the 5.0% petroleum royalty accorded to it.

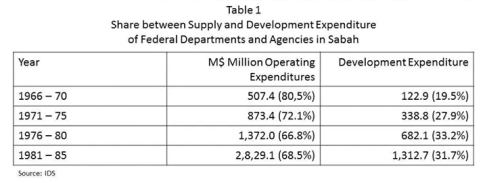

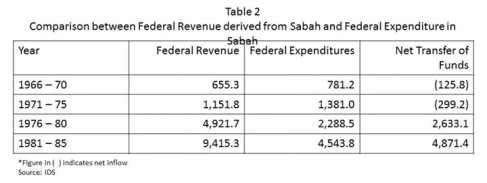

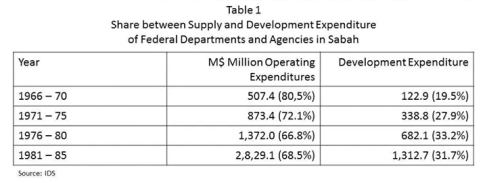

A study conducted by Institute of Development Studies (Sabah) concludes that since 1976 there was a net transfer of financial resources out of Sabah in favour of the Federal government. It should also be borne in mind that much of the Federal government’s financial flow to Sabah has actually been in the form of operating expenditures to service the large numbers of federalised agencies in Sabah. Although, during the First and Second Malaysia Plan period the Federal government had spent more in Sabah than collected from it, however, since 1976 there has been a net outflow of funds from Sabah to the Federal government amounting to M$2,633.18 million in the Third Malaysia Plan period and M$4,871.46 million during the Fourth Malaysia Plan period. During the First, Second, Third and Fourth Malaysia Plan period, some 80.5%, 72.1%, 66.8% and 68.3% of the financial allocation to Sabah were for operating expenditures of Federal departments and agencies as shown below:

The substantial net outflow of funds from Sabah to Kuala Lumpur is perceived by Sabahans as siphoning off of Sabah’s development funds which is tantamount to financial exploitation of the State.

The understanding of the leaders in joining Malaysia was to achieve an accelerated pace of economic development. However, it appears that the bulk of the Federal funds currently spent in Sabah are for operating expenditures rather than for development purposes.

The overall level of financial allocation to Sabah by the Federal government can be considered as minimal relative to its socio-economic development needs. These allocations are indeed meagre when compared with the amount of financial resources derived by the Federal government from the State as shown by the table above.

It is further felt that the State’s share of its oil revenue (5%) is too small. The sequence of events which led Sabah to sign away its oil rights to the Federal government has continued to puzzle the minds of the Sabahans. Previous Chief Minister, Tun Mustapha and Tun Stephens had consistently refused to sign the Petroleum Sharing Agreement indicating their unwillingness to give up the State’s oil rights. It is interesting to note, however, that in the ensuing political crisis following immediately after the June 6, 1976 plane crash resulting in the death of most of the key BERJAYA leaders, Datuk Harris Salleh dramatically reversed the position of the State government by signing away the State’s oil rights.

To many Sabahans the signing away of Sabah’s oil rights is equivalent to Constitutional amendment. Many believe that unless approved by the State Assembly with a two-third majority, the Chief Minister’s signature alone does not constitute approval of the people of Sabah.

22.12 Point 12: Special Position of Indigenous Races

In principle, the indigenous races of North Borneo should enjoy special rights analogous to those enjoyed by Malay in Malaya, but the present Malaya formula in this regard is not necessarily applicable in North Borneo.

Comments:

While in principle the special privileges of Sabahan natives are recognised legally, the implementation of the policy has been somewhat dubious. For instance, when job vacancies in Semenanjung are advertised in national newspapers to the effect that “preference shall be given to bumiputera”, what it in effect implies is bumiputera of Malay origin and, inevitably the Malay in Semenanjung. This legacy was exported to Sabah during the reign of the government of Tun Mustapha and Datuk Harris. It is well-known that during those periods, the treatment accorded to indigenous people in the State depended on their religious faith. This gave rise to two categories of indigenous people – Muslim indigenous and non-Muslim indigenous. These actions always done in the name of ‘integration’ with the aim of presenting Kuala Lumpur the impression that the Muslim population in the State had grown rapidly. There were numerous cases during the reign of the previous governments where non-Muslim bumiputeras especially the Kadazans and Muruts, were bypassed for promotion or recruitment into the civil service unless they became Muslim.

22.13 Point 13: State Government

(a) The Chief Minister should be elected by unofficial members of Legislative Council;

(b) There should be a proper Ministerial system in North Borneo.

Comments:

The incorporation of this point in the IGC Report and Federal Constitution was consistent with the original intentions of the Sabah leaders.

22.14 Point 14: Transitional Period

This should be seven years and during such period legislative power must be left with the state of North Borneo by the Constitution and not merely delegated to the State government by the Federal government.

Comments:

This point was not addressed in the Malaysia Agreement nor dealt with in the Federal Constitution, even though the Cobbold Commission studied the point and recommended that the transitional period should be five years, or alternatively, minimum three years and maximum seven years. The ‘Transitional Period’ is actually discussed in Para 34 of the IGC Report and partly in Annex A to the Report.

It was clear that the purpose of introducing the transitional period was to provide the much needed time for the growth of political consciousness among the people of Sabah so that they would be able to understand their roles and responsibilities as political leaders. Both Malaya and Singapore had experienced a period of self-rule before Independence. Since neither Sabah nor Sarawak had any form of political relationship with Malaya and Singapore before the formation of Malaysia, a trial period would have significantly improved the Federal-State relationship right from the beginning. Had the transitional period been effected, it is generally believed that the erosion of constitutional safeguards may not have occurred so easily and rapidly.

22.15 Point 15: Education

The existing educational system of North Borneo should be maintained and for this reason it should be under State Control.

Comments:

The existing educational system referred to primary and secondary schools and teachers training colleges, but not university and post-graduate education. The Sabah delegation wanted to teach English at all levels of schools in the State as the medium of instruction. Malay and other vernacular languages, such as Kadazan and Chinese, were also to be taught and used as the media of instruction in lower level primary schools in some primary schools in some voluntary agency schools. It was the intention that the education policy and its development will be subject to constant adaption and would move towards a national concept but it should not merely be an extension of existing Federal policy.

In the IGC Report education was a federal subject although specific conditions were spelt out for its administration. The IGC Report also specified important conditions pertaining to education development in general including the use of English and implementation of indigenous education.

In 1965, the Sabah Education Ordinance No.9 of 1961 was declared a federal law. During Tun Mustapha’s reign, the State Constitution was amended to make way for the use of Malay as the sole official language by 1973. When the Peninsular introduced Malay as the medium of instruction in Primary One in 1970, Tun Mustapha’s Administration adopted the same policy in Sabah.

Since the Education Act, 1961, was extended to Sabah only in 1976, the introduction of the national Educational Policy to Sabah in late 60s and early 70s with the tacit consent of the then State government under Tun Mustapha was carried out without the proper legal authorities. However, this has been rectified by the extension of the Education Act, 1961.

It is also important to note that the IGC Report made specific references to the responsibilities of the Federal government in developing educational infrastructure in Malaysia, “the requirement of the Borneo States should be given special consideration and the desirability of locating some of the institutions in the Borneo States should be borne in mind.” By and large, the Federal government has done little for Sabah in the development of higher education facilities, aside from the setting up of a YS-ITM campus and a makeshift UKM branch campus. Even a donation by the State government of 364 hectares of land in 1980 to be developed into a permanent campus of the UKM together with a $5.0 million contribution from Yayasan Sabah failed to elicit the “special consideration” responsibility of the Federal government on the development of education infrastructure in Sabah as contained in the IGC Report.

Yet in Kedah, Universiti Utara Malaysia which was only established in 1984 enjoys the full financing and other support of the Federal government as compared to the Sabah branch of UKM which was established in 1974, or then years earlier.

Such a phenomenon does not only violate the “special consideration” clause supposedly accorded to Sabah but it also speaks of the inequity in the distribution of funds for educational purposes among components parts of the Federation of Malaysia.

22.16 Point 16: Constitutional Safeguard

No amendment, modification or withdrawal of any special safeguard granted to North Borneo should be made by the Central government without the positive concurrence of the government of the State of North Borneo. The power of amending the Constitution of the State of North Borneo should belong exclusively to the people in the State.

Comments:

Most of the safeguards contained in the IGC Report were incorporated into the Malaysia Agreement and subsequently into the Federal Constitution, although a number of these have since been repealed. In addition to the provision in the Constitution, Article VIII of the Malaysia Agreement provides that the governments of the Federation of Malaya, North Borneo and Sarawak will take such legislative, executive or other action as may be required to implement the assurances, undertakings and recommendations contained in Chapter 3 of, and Annexes A and B to, the Report of the IGC signed on 27th February, 1963, in so far as they are not implemented by expressed provision of the Constitution of Malaysia.

An additional important agreement reached by the IGC was that certain aspects of the requirements of Sabah could appropriately be met by undertakings or assurances to be given by the government of the Federation of Malaya rather than by Constitutional provision. The Committee further agreed that these undertakings and assurances could be included in formal agreement or could be dealt with in exchanges of letters between the governments concerned.

In the minds of the people of Sabah (and Sarawak), the inclusion of the safeguards in the Constitution was reassuring in that they were as good as guaranteed by the British government. There is, however, an oversight by those responsible for drafting the Constitution to ensure that these safeguards are to be really effective. An amendment to the Federal Constitution must be passed by a two-third majority by the Parliament (which in today’s composition of Parliament is a non-issue) and, where State rights are involved, it must have the consent of the State government concerned (i.e. the Executive). It does not have to be approved by the State Assembly (the representatives of the people of the State) by also a two-third majority. Under the present Constitutional arrangements, thesafeguards are therefore as good only as the strength or personality of the State government of the day.

In essence, most of the safeguards can be abrogated by the mere ‘consent’ of the State government of the day, even for the sake of wanting to ‘please’ the Federal government. There is a general belief that this had been the case for previous governments in Sabah.

Para 30 of the IGC Report and Article 161E of the Federal Constitution provide the constitutional safeguards on some specific matters. While, Article 161E is not exhaustive, these are safeguards found in other constitutional provisions. Amendment to Article 3(3) (making the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong the Head of Islamic religion in Sabah) and repealed og Article 161A(1)(2)&(3) (relating to the special position of the Natives of Sabah) and Article 161D (relating to freedom of religion in the State) if made without the concurrence of the Yang Di-Pertuan Negeri contravenes Article 161E.

It should be pointed out that there are also cases where the Federal government failed to seek the concurrence of the State government in making amendments relating to matters under State control.

As regards Fisheries Act, 1985, marine and estuarine fishing and fisheries are in the Concurrent List whereas riverine and inland fishing and fisheries and turtles are in the State List. Therefore, both the State and Federal Legislatures can pass law on the former but only the State Legislature can pass law on the latter (except for the purpose of uniformity; but in such cases the law only come into force in the State if adopted by the State Legislature). In the event of conflict between State and Federal laws, the Federal Law will prevail. However, Sabah has its own Fishing Ordinance, 1963, but this was repealed by PUA 274/72 under section 74 of the Malaysia Act, 1963 apparently without the consent of the Head of State (Yang Di-Pertuan Negeri)

Similarly, when the Federal government put fishery matters as a supplement to the Concurrent List taken away from the State in 1976, concurrence was not sought from the State government. And when the Federal government repealed the Fishery Ordinance in 1978, again the State government was ignored. The Fisheries Department in Sabah is now in danger of being sued by the public because it is enforcing law upon which it has no power to it.

22.17 Point 17: Representation in Federal Parliament

This should take account not only of the population of North Borneo but also of its size and potentialities and in any case should not be less than that of Singapore.

Comments:

This point was taken up in the IGC Report and Malaysia Agreement. However, it is important to stress the fact that when considering representation in the Federal Parliament, the potentialities of Sabah should be taken into account and that the mention of the size of Singapore’s representation was only the minimum requirement. There are now 20 members from Sabah in the lower house of the Parliament. This particular point therefore remains ‘unbroken’. But since the signatories of the Malaysia Agreement consisted of the four governments of Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak and Sabah, there is a strong case for arguing that the matter should have been reviewed when Singapore pulled out from the Federation of Malaysia.

Indeed in view of Singapore’s departure from the Federation this safeguards must be reviewed along with other assurances in order to give the Malaysia Agreement validity. This review should be made immediately if Malaysia, as a federation, is to continue to be valid.

22.18 Point 18: Name of Head of State

Yang DiPertua Negara

Comments:

The name of the Head of State is Yang DiPertuan Negeri, as opposed to Yang DiPertua Negara as contained in both the Twenty Points and IGC Report. The use of the word ‘Negara’ by the Sabah leaders seems to convey the point that in their minds, independence was to bring with it a certain level of political autonomy for Sabah. It may therefore be argued that Sabah upon joining the Federation was a ‘negara’ or a nation. This clause was amended in 1976 in the Federal Constitution. Hence, the fact that this provision is not followed is a clear deviation.

22.19 Point 19: Name of State

Sabah

Comments:

This point was taken up in both the IGC Report and Malaysia Agreement.

22.20 Point 20: Land, Forest, Local Government etc.

The provision in the Constitution of the Federation in respect of the power of the National Land Council should not apply in North Borneo. Likewise the National Council for Local Government should not apply in North Borneo.

Comments:

While the State continue to exercise control over land, agriculture and forestry, the Federal government has established a National Land Council whose intention is yet to be determined. Should the National Land Council extend its jurisdiction over Sabah then it will contravene this particular provision.

23. In conclusion, it is shown that there are a number of critical areas in which the Federal government has deviated from the original spirit and meaning of the constitutional safeguards and assurances granted to Sabah at the formation of Malaysia. The basic conditions were contained in the memorandum called the “Twenty Points”, the contents of which were subsequently incorporated into the IGC Report, the Malaysia Agreement and Federal Constitution. The principle areas in which there have been clear deviations with respect to implementation are those which relate to matters pertaining to Immigration, Religious freedom, Borneonisation, Citizenship, Education, Finance, and Tariff Arrangements and Constitutional safeguards.

24. Deviations in implementation with respect to these matters have been largely responsible for strained Federal-State relations, thereby presenting barriers for territorial integration. It must nevertheless be stressed that problems pertaining to Federal-State relations do not originate merely from deviations as described above. Equally important is the problem of political interference by Kuala Lumpur in State affairs.

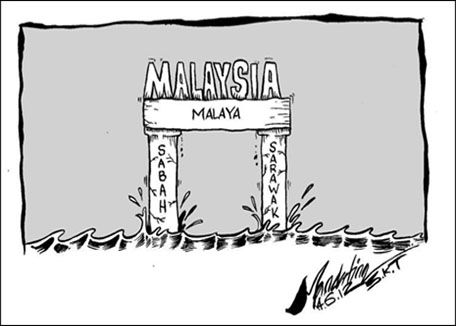

As a result of the deviations and political interferences, an idea is now slowly taking root that there is going to be a ‘take-over’ of the Borneo Territories by Malaya and the submersion of the individualities of Sabah and Sarawak.

V. FORM OF INTERFERENCE IN STATE AFFAIRS

25. Although much publicity was given to the status that Sabah would enjoy in the proposed Federation and the range of safeguards that would be granted to the State, the interference of the Federal government in State affairs actually commenced within months of the birth of the Malaysia nation. The saga began with the tussle for control of the State government between Tun Fuad and Tun Mustapha, the outcome of which was dictated by Kuala Lumpur. Paul Raffaele in his book Harris Salleh of Sabah gives an accurate assessment of the event:

“… Although the early leaders of Sabah had hoped that Malaysia would be a true Federation and not a unitary state, post-independence history has shown that when the interests of Sabah and Kuala Lumpur clash, the Federal government will step in unhesistantly and bring its younger partner to heel. Tunku Abdul Rahman saw the Kadazan Chief Minister as less than totally committed to Malaysia, unlike his friend Mustapha who saw the new Federation as giving power support to his claim of Malay and Muslim political primacy in Sabah” (Raffaele, 1986, p.30)

26. The details of the events surrounding the Mustapha-Fuad crisis are well documented in history books. Suffice it to say that the difference between the two leaders lie in the fact that while Tun Fuad Stephens was jealously guarding the State’s rights in pursuance of the original safeguards and promises, Tun Mustapha was more interested in strengthening Islam and developing Malay dominance in Sabah, regardless of its effects on state affairs. Numerous clashes between the two leaders can be traced to these fundamental differences in outlook and orientation. For instance, Tun Mustapha refused to approve the appointment of John Dusing as State Secretary, in contravention of the behaviour of a constitutional Head of State. However, all this was done with the help of the Federal Secretary in the person of Mr. Yeap Kee Aik whose major role was to strengthen Kuala Lumpur’s hold on the frontier State, by ensuring that “any party favouring Malaysia should prosper while being unfavourably disposed to any party that seem to have doubts about the Federation” (Raffaele, 1986,pp. 142-144)

27. This has led some scholars to describe the 20 Points safeguard as follows:

“The intent of the safeguards was to give State leaders the illusion of having greater control than they in fact possessed, but illusions which they were to take very seriously.”(Ross-Larson, 1980).

28. The Mustapha-Stephens crisis can be aptly described as follows:

“The two (referring to Tun Mustapha and Tun Fuad Stephens) were unwitting actors in a drama written by the Federal government, and both felt compelled to play out their roles, however reluctantly.” (Ross-Larson, 1980)

29. The hands of the Federal government in shaping the political development and accelerating the erosion of State’s constitutional safeguards, can be clearly seen in the selection, encouragement and support for a state leader who reflected the Federal cause, who in the immediate years after Independence was none other than Tun Mustapha. In order to further ensure that the new State government would not be too independent-minded and thereby jeopardise federal’s interests in the State, Syed Kechik, a strong UMNO supporter and the political secretary to the Minister of Information, was assigned to assist Tun Mustapha. Syed Kechik’s contributions included the introduction of various constitutional amendments and new laws to shift the power from the State to the Federal government. It is believed that he was also instrumental in the resignation of top civil servants who were thought to be pro-state and their replacement by Federal sympathizers.

30. Whenever the question of who should bear the responsibilities for the erosion of the constitutional safeguards is raised, the standard answer is that it was the doings of the Sabah leaders themselves. However, history has shown that during the USNO’s rule the erosion of constitutional safeguards on education, language and religion can be directly traced to machinations of Kuala Lumpur’s appointees including Syed Kechik, the then Attorney General of Sabah and other Federal officers who were unsympathetic and unmindful of their far-reaching consequences on the State.

31. For the sake of harmonious and enduring Federal-State relationship in the future, the Federal government has as much obligation as the State government in upholding the constitutional safeguards.

32. In instances where erosion of constitutional safeguards has occurred either unwittingly or erroneously, the parties involved should take steps to restore such rights, otherwise inaction would be interpreted as a deliberate scheme to weaken the power of the other party.

33. In the final years before the rise of BERJAYA in 1976, Tun Mustapha began to lose favour with the Federal government. This was primarily because of the misuse of his draconian powers, bestowed on him originally by the Federal government, which eventually made him a political liability to Kuala Lumpur. His plan to break away from the Federation by proposing the formation of Borneosia and establish his sultanate was also an important factor which contributed to his fall from the grace of the Federal government. But by then, Tun Mustapha had paved the way for the erosion of the safeguards on Education, Language and Religion. Throughout his regime, the Federal government essentially abandoned the people of Sabah to his abuse of their democratic rights and his squandering of the State’s natural resources. When political intervention would have been justified, and indeed was most needed, Kuala Lumpur opted to assume a spectator’s role to the great disappointment of the people of Sabah.

34. The emergence of BERJAYA and the success it had in deposing the regime of Tun Mustapha occurred with the support of the Tun Razak government. In its early stage of development, the party sought earnestly to reverse the excesses of Tun Mustapha. However, when its leaders were assured of deriving support from the Federal government, it committed the same excesses as its predecessor. As with Tun Mustapha’s Administration, the Harris’ Administration became increasingly more autocratic and intolerant to well-intended public criticisms. It distanced itself from the Rakyat by pursuing policy objectives contrary to the wishes and aspirations of the people. It had even gone to the extent of changing the district status of Tambunan just to punish the voters who defied his order to support him. His abuse of power included the liberal use of Federal and State machineries in the 1985 general elections campaigns.

35. In the ensuing years Datuk Harris’ Government committed other political excesses similar to those of his predecessor. The problem of illegal entrants obtaining blue IC became increasingly more acute without his government doing something about the problem. Datuk Harris’ Government promoted massive conversion to Islam among indigenous Sabahans by granting favours to prospective converts. His government’s desire to keep the Federal happy culminated in the signing away of Labuan, free of charge, without the consent of the people of Sabah, although on the surface the federalisation of Labuan appeared to have been properly executed by subtly forcing an enactment through the State assembly. The act was also a breach to the Twenty Points safeguards.

36. When the PBS came into power, the Federal government could not accept the defeat of the party that had been so accommodating to Kuala Lumpur’s drive towards a unitary state. Amidst the events that followed the power grab at the Istana until the next general State elections in 1986, when the people of Sabah were forced to give their verdict on the legality of the government of the day, traces of Kuala Lumpur’s involvement were obvious. The fact that those involved in the power grab were let loose caused many Malaysians to take a dim view of the rule of Law as there was a clear case of miscarriage of justice. Between April 21, 1985 and May 5, 1986, two State general elections were held in close succession because of the reluctance of certain Federal leaders in endorsing the results of the 1985 general elections which saw the defeat of the Federal-anointed party. Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr. Mahathir Mohammed when interviewed about the unsettled political climate in Sabah, was widely reported to have said that he himself was not sure as to which government, the ruling PBS Government or the contending USNO-BERJAYA coalition Government, would the Court uphold as the duly elected government of the people of Sabah.

37. It is amazing that the vanquished parties even had the audacity to hail the victor to court and demanded that they be installed to replace the rightfully elected government by claiming to represent the wishes of the majority of the people. While the people of Sabah were fearing for their lives, no decisive action was taken by Federal Government until the tense situation escalated into outbreak of lawlessness causing losses of property and lives. When those responsible were finally brought before the courts the charges handed out were viewed by Sabahans as a mockery vis-à-vis the extent of damages, human tragedy and economic losses caused by the rioters. Indeed, there were broad hints that some quarters were using the March 1986 riots to justify the imposition of Emergency rule in sabah by the Federal government, as a way to replace the democratically elected government.

38. Finally, many Sabahans consider the proposed entry of the UMNO into Sabah as not entirely unrelated to the issue of political interference. While the move has been cast in the name of championing Muslim cause and so-called bumiputera rights, the timing of the exercise and the past records of Kuala Lumpur’s interference in State affairs leave many nationalistic Malaysians of local origin unconvinced that the move will lead to any enhancement of Federal-State relations. Indeed Sabahans take the view that the whole exercise will be detrimental to national unity because the promotion of communal politics in Sabah will bring about racial and religious polarisation and split the already well-integrated people of Sabah. In the long term, communal politics go against the spirit of multiracialism which the Sabah leaders have so tirelessly championed. The proposed move of UMNO into Sabah also indicates the lack of understanding by the Federal leadership on the socio-cultural and psychological makeup of the people of Sabah. Unlike the people in Peninsular Malaysia, where people can be conveniently classified into Malays, Chinese and Indians, in Sabah, the racial and religious differences are unimportant as they are already well integrated.

39. It is to be noted that Malaysians in Sabah as represented by their leaders and political parties, have proven their ability to govern Sabah themselves for the past 23 years since the formation of Malaysia, without the presence of any Peninsular party or parties.

40. There is no need for UMNO, PAS, DAP or any other Peninsular parties to come to Sabah. It would be redundant. The important thing is for Kuala Lumpur to be able to foster and work with the ruling group in Sabah and Sarawak.

VI. PROPOSAL FOR STRENGTHENING FEDERAL-STATE RELATIONS

41. This Memo would be incomplete if it only seeks to expose areas of deviation with respect to the Federal Government’s responsibilities in building a united Malaysia by merely highlighting the source of grievances between the people of Sabah and the Federal government. The fact that there have been clear cases of deviations in the implementation of the safeguards and assurances granted to Sabah in 1963 shows that the Federal government must seek to correct them for the sake of territorial integration.

42. In order to build strong Malaysian nation and to restore the people’s confidence in the existing Federal framework, the following measures should be considered and implemented by all parties:

(a) Accept and sustain the principle that Sabah, Sarawak, Singapore and Malaya formed the Federation of Malaysia as equal partners.

(b) As equal partners in the Federation, the revenue of the Federation should be shared equally among the three territories regardless of their population size.

(c) Parliamentary representation should also base on the concept of equal partnership, i.e. total seats divided by three to be effected immediately.

(d) With the expulsion of Singapore, both territories should now be granted equal representation in the Parliament in order to protect themselves against the passage of any laws detrimental to their respective position in the Federation. At the minimum, the total number of seats for Sabah and Sarawak should not be less than those of Peninsular Malaysia (Malaya).

(e) To afford the leaders of Sabah and Sarawak an opportunity in governing the Federation, there should be three Deputy Prime Minister in Malaysia, with one each appointed from Malaya, Sabah and Sarawak.

(f) The Federal leaders should resist, at all cost, the urge towards making Malaysia a unitary state. If one examines the patterns of political developments in Malaysia in recent years, one can easily discern a strong and unmistaken drive, championed mainly by the existing dominant political party within Barisan Nasional, towards making Malaysia a Unitary Government. To materialize such a concept, various means have been employed, some subtle others less polished. Fortunately, the leaders of Sabah and Sarawak are now more educated to realize the negative consequences of this trend. Any form of imposition or political assault, harmful to the State, no matter how sweetly coated and cleverly disguised can be easily detected. This kind of approach is now outdated. It would be in the interest of the new Malaysian nation for leaders to be more frank by solving their problems through direct dialogue and negotiations instead of scheming against one another.

(g) The ruling party, UMNO should stop interfering with Sabah’s politics. Since both USNO and PBS are members of Barisan Nasional, there is no necessity for UMNO to spread its wings to Sabah, unless, of course, UMNO has other ulterior motives.

(h) Instead of categorizing the people of Sabah narrowly according to their ethnic origins, the Federal leaders should help to forge a common Malaysian identity. All attempts should be made to prevent the disease of communal politics from spreading to Sabah.

(i) As a plural society, the right goal for Malaysia should be towards a Malaysian Malaysia.

(j) The pursuit of religious and cultural freedom and economic liberalism should continue. To be consistent with democracy, a market economy, a Malaysian Malaysia, and the 20 Points Safeguard, there should be no official religion in the State. Under this condition, all religious groups will be given the same treatment by the State government. As a result, discriminatory practices which exist at the moment will end. Peace and religious harmony in Sabah will then return once more because people are treated equally. While the use of Bahasa Malaysia as the National Language of Malaysia is acceptable, ample opportunities to learn and practice other languages, including English, Chinese, Kadazan, Murut and other indigenous dialects should be guaranteed by the Federal government. Otherwise, the rich and varied cultural heritage which we have so proudly inherited from our forefathers may be permanently lost a few generations from now. Such a loss will be irreparable. It would be unthinkable to wipe out local cultural roots just because of their lack of numerical strengths from the surface of the earth. If so much efforts have been made by the world community to preserve a near extinct wildlife, how much more should we value human culture.

43. The Federal government must seek to uphold the spirit and intent of granting independence to Sabah through Malaysia. This means respecting and honouring the assurances, promises and safeguards made by the Federal and State leaders to the people of Sabah as contained in the original Twenty Points and as subsequently incorporated in the IGC Report, Malaysia Agreement and Federal Constitution.

44. The Federal government must re-examine the identified areas of deviations with the view to correcting them. Where the intention of introducing constitutional amendments is for the purpose of standardisation, then serious considerations should be given to the aspirations and expectations of the people of Sabah before considering changing them.

45. All present constitutional and financial arrangements should be reviewed and the Federal government should proceed to decentralise Federal functions. Integration must not be viewed and misconstrued as centralisation. In order to reduce redtapes and arrest the rapid increase in operating expenditures (both State and Federal), the functions of certain Federal agencies and departments in the State should be delegated to the State or State agencies. Although such an undertaking may involve to re-organisation of existing Federal and State agencies, the efforts would pay off handsomely as it will result in significant reduction in the level of operating expenditures. By so doing, more financial resources can be devoted to fund development projects.

46. When the states of Sarawak, Singapore and Sabah joined the Federation of Malaya to form Malaysia, as a group, they were given representation in the Federal Parliament in such a manner that the Malayan component on its own would not be able to introduce constitutional amendments affecting the interests of the other three member states without their explicit support. However, with the expulsion of Singapore in 1965, the seats previously assigned to Singapore were not redistributed to Sabah or Sarawak. The power equation has now tilted in favour of Malaya, thus allowing it to introduce constitutional changes unilaterally without the necessity of consulting with Sabah and Sarawak. The consequences of such shift in power equation have effectively weakened the position of Sabah and Sarawak in the Federation. It is recommended that the seats previously assigned to Singapore be redistributed to Sabah and Sarawak, including the possible increase in seat allocation had Singapore remained in the Federation.

47. In pursuing desirable modes of national integration between Sabah and other parts of Malaysia, the Federal government must seek to:

(a) Uphold constitutional arrangements rather than political patronage;

(b) Strive for a more equitable allocation of development funds among members of the Federation for economic and social development. Greater effort must be directed at reducing regional disparities and accelerating social infrastructure development such as the enhancement of medical and education facilities, particularly in lesser developed regions like Sabah and Sarawak.

In the particular context of Sabah and Sarawak, there is a clear case for a fairer revenue-sharing arrangement. Indeed it could be argued that since Sabah and Sarawak formed the Federation as equal partners, the national economic cake should be divided equally among the three principal members (i.e. Sabah, Sarawak and the Peninsula). Notwithstanding recommendations in 42(b), as a compromise, an acceptable revenue-sharing arrangement could be in the form of 50% and 25% each for Sabah and Sarawak. Of course, this view may not be quite consistent with the complex in which revenue is shared in the contact of a typical nation built upon the conventional framework of a federation. But the very concept of “equal partnership” in the Federation, as conceived by Tunku Abdul Rahman, behoves that Sabah deserves better financial treatment than what it is currently receiving as one of the thirteen states. The position that Sabah should be treated as equal partner with Singapore, Sarawak and Malaya in the Federation of Malaysia, was broached to the early leaders of Sabah.

“Both the Tunku and Singapore’s Lee Kwan Yew… were anxious for the Borneo territories to join Malaysia… and were willing to offer North Borneo a special status within the Federation. North Borneo would be an equal partner with Malaya in a true federation and not just one of the Malaysian states.” (Paul Raffaele, 1986, p.96)

48. This unfair treatment must be corrected both by reviewing existing arrangements of revenue-sharing and resource allocation and by increasing the low level of royalty which the State presently receives from oil exploration by the Federal government from Sabah waters.

49. It is recommended that the Federal government seeks to educate school children, civil servants and the general public on the history of formation of Malaysia. It is essential to explain why Sabah and Sarawak should be treated differently from other States in Peninsular Malaysia (Malaya).

50. As a sincere gesture of its intention to treat Sabah and Sarawak as equal partners, it is recommended that the Federal government should make provisions for more leaders from both States to be represented in the Federal Cabinet.

51. In this regards, the example of Singapore when it was a component of Malaysia should be followed. The three component parts of Malaysia should each have a deputy Prime Minister or premier (Australian example) in order that the equal partnership status is actualized. By introducing such a change the people in both territories would develop trust and confidence in the sincerity of the Federal leadership in wanting to help Sabah develop and to grant autonomous powers to Sabah as promised.